PLANTS

©Saxon Holt/PhotoBotanic; Sticky yellow monkey-flower (Diplacus aurantiacus) and other native and drought tolerant perennials.

What is a “Fire-Resistant” Plant?

Fire-resistant plants are those that do not readily ignite from a flame or other ignition sources. These plants can be damaged or even killed by fire; however, their foliage and stems do not significantly contribute to the fuel and fire’s intensity. There are several other significant factors that influence the fire characteristics of plants, including plant moisture content, age, total volume, dead material, and chemical content.

Plant lists can be misleading, giving the homeowner or landscape designer the impression that fire-safe landscaping is just about choosing the right species and avoiding the wrong ones. The reality is that landscape maintenance is essential and any plants can burn under the right conditions. A well maintained, irrigated ‘flammable’ plant can represent a lower ignition risk than a neglected ‘firesafe’ plant. Because any plant species can burn, we focus instead on the underlying principles behind designing a fire-safe home and landscape, and on maintaining structures and plants properly.

Conditions Over Species

Remember that the condition of the plant is often as important as its species. Many fire-hazardous plants can be relatively ignition-resistant if properly maintained and irrigated, especially natives. Depending on its growth form and access to water, the same species may be ignition resistant in one environment and flammable in another. Water-stressed plants in poor condition are more likely to burn readily. Those species already identified as fire-hazardous may become explosively flammable when poorly maintained. South-facing slopes, windy areas, sites with poor soils and urban landscapes are more stressful for plants and often lead to greater hazard from burning vegetation.

Fire-Hazardous Plant Characteristics

Plant Characteristics That Make the Vegetation Vulnerable to Burning, or Prone to Igniting and Carrying Flames.

Learn to identify fire-hazardous plants by their characteristics, structure, and maintenance. This is not an exhaustive list, and some plants not listed here may present a fire hazard when drought stressed or poorly maintained. Any plant in poor health, lacking irrigation, or with a buildup of dry or dead material may burn. Most common fire-hazardous plants typically share certain characteristics:

- Plants that are summer-dormant unless being watered year-round (e.g., sagebrush, sages, etc.).

- Plants that produce dry leaf-litter and duff that accumulates atop the soil and on other plants in the vicinity.

- Trees and shrubs with dry, peeling bark.

- Trees and shrubs that retain clusters of dead leaves/branches/fronds (e.g., palms, eucalyptus, Italian cypress).

- Dry grasses that grow green in the winter and turn yellow/brown in the summer.

Plant Characteristics and Maintenance Steps to Reduce Ignition Risk

- There are no “fire-proof” plants. Select high-moisture plants that grow close to the ground and have a low sap or resin content.

- Plants that are regularly watered, reducing dead leaves/duff production.

- Large, green trees and shrubs maintained without dead branches and clusters of dead leaves (e.g. coast live oaks that can act as a shield against flying embers).

- Plants with high moisture content and easily bent leaves.

- Plants with thick leaves.

- Plants without fragrance.

- Plants with silver or gray leaves.

- Plant leaves without hair.

©2010 Calscape; Flowers of California redbud (Cercis occidentalis).

Here are some examples of fire-resistant native plants for you.

Some of our favorite California natives are also fire-resistant. Here is a list you might want to consider. We’ve included the scientific names, because that is often how the plants are listed in government guides to fire-resistant varieties.

Important Note: All plants will eventually burn. There is no such thing as a fireproof plant. There are some plants that can retain moisture, even in dry areas, and are called fire resistant. This list is designed to identify some Californian native plants that are fire resistant and have wildlife value. The purpose of this list is to help place fire-resistant and wildlife important plants in areas where brush clearance can leave an area barren.

Photos of the plants listed are courtesy of the California Native Plant Society and the Theodore Payne Foundation.

Trees

|

Toyon |

California Sycamore |

Coast Live Oak |

||

|

|

|

||

| A classic California native, it has white flowers in the summer and berries in the winter, it gets good marks from Los Angeles, Orange, San Diego and the Inland Empire. | Sycamores have delighted generations of Californians, and this particular variety is endorsed for use by the Los Angeles and Orange County fire departments, plus San Diego County. | Handsome shade tree. Round-headed with dense foliage, grows 20-70 feet tall. Smooth, dark grey bark, with leathery dark green leaves. Native to coastal central and Southern California. |

Shrubs

|

Common Yarrow |

Quail Bush |

Coyote Bush |

||

|

|

|

||

| It appears on fire-resistant lists for California Native Plant Society, Western MWD (zone 3), San Diego County, and Orange County fire. However it is not on the approved list for Los Angeles County fire. Yarrow also can be used as a groundcover if mowed. | Big Saltbush / Quail Bush is native to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, where it grows in habitats with saline or alkaline soils, such as salt flats and dry lake beds, coastline, and desert scrub. This plant is used to revegetate riparian habitat in its native range. Big saltbush produces abundant seeds and is demonstrably fire resistant | Coyotebrush is moderately fire tolerant. It is a common shrub in the Asteraceae that grows in California, Oregon, and Baja California. All forms of this shrub are generally 1-3 meters in height. Coyote Brush is extremely easy to grow in landscape applications. It tolerates summer water up to weekly, but naturalizes easily also. |

|

California Lilac |

California Redbud |

Island Bush Snapdragon |

||

|

|

|

||

| This California lilac is a large shrub with a dense mass of dark green, 1-inch leaves, with dark blue clusters of flowers appearing in spring. Requires good drainage; can tolerate summer water. Grows to six feet. | An interesting plant all year long, with magenta flowers on leafless stems in summer, followed by crimson seedpods and heart-shaped blue-green leaves. Deciduous, with yellow or red fall foliage falling away in winter to reveal smooth reddish brown trunks. Long lived, very drought tolerant, and flowers more profusely as it matures. | This CNPS “rare” plant is from the Channel Islands andstays evergreen year round producing trumpet shape red flowers favored by hummingbirds. It grows in 18” to 24” in height and 3’ to 5’ in width. It also adds excellent cover for wildlife. |

|

Bladderpod |

Nevin’s Barberry |

Mahonia/ Barberry |

||

|

|

|

||

| Bladderpod is one of the easiest California natives to grow in landscape applications. The flowers are beautiful, bright yellow, and stay on the plant most of the year, and attract bees, butterflies and hummingbirds. It is highly fragrant, though the public is divided on whether it is pleasant or unpleasant. Bladderpod is considered a fire retardant plant by the Los Angeles State and County Arboretum’s Fire Retardant Plant Research Project. | A federally endangered species, once common in the Verdugo Mountains, grows berries that are favored by many songbirds. The spiny leaves also add a protective cover. The shrub can grow up to 4’ in height and 6’ in width and is evergreen. (LA County Fire approved) | It’s purple berries and yellow flowers are favored by many songbirds. The spiny leaves also add a protective cover. (LA County Fire approved) |

|

Monkey Flower |

Beard Tongue |

Guadalupe Island Rock Daisy |

||

|

|

|

||

| Monkey Flower is an evergreen shrub 18 in. to 3 ft. with numerous tubular flowers. It is a California native that is drought tolerant. It attracts hummingbirds. The entire species is endorsed for use by San Diego County planners and the Los Angeles and Orange County fire departments. | This particular variety is native to the Southland, but the entire species has been embraced by native plant enthusiasts and firefighters alike, and is approved for use in L.A., Orange and San Diego counties. | Dependable plant with attractive silver foliage that contrasts beautifully with darker foliage of Ceanothus and Rhamnus. Panicles of bright yellow flowers shroud the plant in spring. Recommended for butterfly gardens. |

|

Lemonade Berry |

Laurel Sumac |

Golden Currant |

||

|

|

|

||

| A very drought-resistant shrub that provides cover and food to wildlife. California Thrasher uses it’s fruit and leaf material for nesting. It also is an excellent erosion control plant. | While laurel sumac does have a high oil content, it has found to have a much higher incineration point than most other plants. It has been found to be one of the last plants to burn in fires. It provides important cover, food and nesting resource for many types of wildlife. A laurel sumac that has the lower third of it’s branches pruned is considered fire-wise. | This currant grows upright to 6’ and is lacy in structure. In summers, it can go semi-drought deciduous, though with some water in will remain evergreen. It’s berries offer a high wildlife value. (LA County Fire approved) |

|

Matilija Poppy |

Sages |

Common Snowberry |

||

|

|

|

||

| Also known as the fried egg plant, this impressive perennial needs plenty of room to spread. It can be difficult to contained once established. Spectacular lightly fragrant flowers. Renew clumps by cutting back to stubs each winter. A show-stopper in late spring! | Nothing evokes California quite like a sage-scented hillside. Salvias are scented due to natural oils and in nature can be flammable. But they are an exception to the avoid planting rule because if you keep them clean and tidy and lightly irrigate them every two weeks it significantly reduces their flammability. This is a good example of how maintenance is key to reducing fire risk and improving habitat quality. | While not the favorite berry choice of most wildlife, it still gets eaten. Its root system is vigorous and deep enough to hold most banks. Snowberry has been seen on Northfacing slopes in the full sun, though shaded areas such as under oaks is best. |

|

California Fuchsia |

||||

Epilobium canum ssp. canum Epilobium canum ssp. canumCalifornia Fuchsia[/caption]The California fuchsia is a showy perennial shrub that grows 1-2 ft. high with upright stems. It has gray-green foliage and bright orange-red tubular flowers and attracts hummingbirds. This shrub is a native to California and is drought tolerant. |

||||

Groundcover

|

Beach Carpet Saltbush |

Four-wing Saltbush |

Dwarf Coyote Bush |

||

|

|

|

||

| A low growing form of saltbush (6” high, spreading). This saltbush provides good ground cover for soil erosion and provides seeds, salt and cover for wildlife. | A low growing form of saltbush (1-2’ high, 3’ wide) that happily grows in the desert. It provides seeds, salt and cover for wildlife. | While not a “showy” plant, it does produce some flowers and has a deep root system, that provides good erosion control. It grows 12” to 18” in height. It adds cover and seeds for a variety of birds. (LA County Fire approved) |

|

Wild Strawberry |

Willowy Coyote Mint |

|||

|

|

|||

| Bay area native, the beach strawberry (F. chilolensis) is a native strawberry that forms a dense green mat 4 inches high spreading by runners and rooting as it goes. White flowers in spring followed by small but edible berries. Quite drought tolerant near the coast where it grows in sand dunes. This species has the rare distinction of being approved by Los Angeles County fire department for any zone in your yard. Woodland strawberry (F. vesca) is the woodland version of the native strawberry. As the beach strawberry gets shaded out this one takes over, a vigorous evergreen ground cover rooting as it goes. | This federally protected coyote mint grows up to 18” tall and prefers North facing (somewhat shaded) or riparian areas. It has a long blooming cycle, flowering through the summer and fall and is an attractant to hummingbirds and butterflies. Songbirds also eat the seeds. |

©2010 Calscape; Hummingbird and Cleveland sage (Salvia clevelandii).

The Habitat Value of YOUR Garden

Native plants are essential ecosystem components and provide habitat for native birds, butterflies and other wildlife. California’s floristic province is known as a global hot-spot for its diversity of unique plants and animals. To preserve our natural heritage it’s important to live responsibly in the WUI.

Of all the many reasons to plant California natives in our gardens – for creating a sense of place, for their beauty and adaptability, for their drought tolerant qualities, and certainly for increasing biodiversity – their ability to help save our ecosystems and the bird and insect species that depend on them is the single most important reason to grow native plants. Suburban, urban, and rural gardens are fast becoming a last refuge for many wildlife species, such as songbirds, butterflies, bees, toads, frogs and other beneficial creatures, that have lost habitat due to human development. In some cases, cultivated gardens that offer a rich diversity of native plants may offer more resources, such as foraging opportunities for birds and other wildlife, than surrounding degraded wild lands.

Fire and Native Plants

Good fire preparation in your landscape can help protect wildlands from damage, but sustainable and fire-wise gardens also conserve water, limit the use of potentially harmful chemicals such as fertilizers and pesticides, and also avoid invasive plant species.

Many native (and CA friendly) plants grow slowly and maintain high levels of moisture in their leaves and stems with little irrigation. By choosing these plants, you can protect the health of neighboring habitat and create a beautiful lower maintenance garden.

We have listed examples of fire-resistant native plants in our section on Plant Characteristics. Remember that all plants will eventually burn. There is no such thing as a fireproof plant. There are some plants that can retain moisture, even in dry areas, and are called fire resistant. These plants are the ones we are sharing with you.

Benefits of Using Native Plants

Benefits of Using Native Plants

Save Water

Once established, many California native plants need minimal irrigation beyond normal rainfall. Saving water conserves a vital, limited resource and saves money, too!

Lower Maintenance

Lower Maintenance

While no landscape is maintenance free, California native plants require significantly less time and resources than common non-native garden plants. California native plants do best with some attention and care in a garden setting, but you can look forward to using less water, little to no fertilizer, little to no pesticides, less pruning, and less of your time.

Pesticide Freedom

Pesticide Freedom

Native plants have developed their own defenses against many pests and diseases. Since most pesticides kill indiscriminately, beneficial insects become secondary targets in the fight against pests. Reducing or eliminating pesticide use lets natural pest control take over and keeps garden toxins out of our creeks and watersheds. For more information about pest management, take a look at our dedicated tab in this section.

Wildlife Viewing

Wildlife Viewing

Native plants, hummingbirds, butterflies, bees, and other beneficial insects are “made for each other.” Research shows that native wildlife clearly prefers native plants. California’s wealth of insect pollinators can improve fruit set in your garden, while a variety of native insects and birds will help keep your landscape free of mosquitoes and plant-eating bugs.

Support Local Ecology

Support Local Ecology

As development replaces natural habitats, planting gardens, parks, and roadsides with California native plants can help provide an important “bridge” to nearby remaining wildlands. Recommend native plants to homeowner associations, neighbors, and civic departments. Get involved in your community and with local land-use planning processes to help preserve our California native plants and wildlife.

©Elisa Read; Western bumble bee (Bombus occidentalis)

The Native “Soil Keepers”

If you live in the Wildland Urban Interface, there is a chance you are surrounded by hills or uneven terrain. To help avoid erosion and runoff on your property, put in some native plants to stabilize the soils, control erosion and reduce your future irrigation costs. Moist and cool months are ideal to start these “soil keepers”. Once established they will require little irrigation. A mixture of plants is best, with various root depths to hold up a slope. In addition, a sprinkling of native seeds will add to the immediate coverage of your slope.

EXAMPLES

Blue-eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium bellum)

Blue-eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium bellum)

Delicate flowers, abundant from February to May, with grass-like leaves. A perennial, found naturally in grass meadows and other open places, re-seeds easily. A lovely addition to a dry border and does well in containers with well-draining soil. Likes sun to partial sun exposure. Foliage will die back in summer heat. 1’h x 1’w

California Fuschia (Epilobium canum or Zauschneria californica)

A very hardy native that can take a lot of abuse, this is commonly found in dry areas, rocky slopes and cliffs. Abundant, scarlet tubular flowers from July to November, popular with hummingbirds. Likes sun to partial sun exposure, may be used as a ground cover. 2’h x 4’w

California Redbud (Cercis occidentalis)

California Redbud (Cercis occidentalis)

An interesting plant year round, with beautiful pea-shaped magenta flowers on leafless stems in the spring, followed by interesting seedpods and heart-shaped bluegreen leaves. Deciduous, with yellow or red fall foliage on multi-branching stems. Prefers sun exposure. Excellent for dry, seldom watered banks. 20’h x 15’w

Twinberry Honeysuckle (Lonicera involucrata)

Twinberry Honeysuckle (Lonicera involucrata)

Prefers moist areas and pruning will keep size under control. Dense foliage with unique orange-red flowers that produce berries, attractive to birds. Blooms in the spring, drops leaves in winter. Sun to partial shade exposure. 6’h x 6’w

©carlfbagge / Flickr; Invasive black mustard (Brassica negra) near Sunken City, San Pedro, CA.

Fire and Invasive Plants

Invasive plants, those non-native species that cause ecological or economic harm, are one of the great threats to the health of Southern California’s Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) areas. Fire and plant invasions are related in several ways. In natural plant communities, the presence of invasive plants can increase the risk of wildfire. For example, invasive plants like giant reed (Arundo donax) can produce a great deal of biomass and then become dormant and dry, thus increasing the intensity and severity of fire, especially in riparian areas where fires are naturally rare and low intensity.

Invasive plants and wildland health

Most plants don’t escape our yards and gardens, but the handful that do can cause serious problems. Animals, wind, and water move plants and seeds far from where they were planted. Once established in natural areas, these plants displace native vegetation and greatly reduce wildlife diversity. Invasive plants also fuel wildfires, contribute to soil erosion, clog streams and rivers, and increase flooding. Poor maintenance of cleared areas can promote their spread. Because they thrive in disturbed soils, improper clearance or over-clearance often leads to a landscape dominated by invasive plants. These plants can produce more fuels than native vegetation, increasing the potential for ignition.

How to recognize invasive species?

When choosing plants for your fire-safe landscape, you can help protect the health of neighboring wildlands by avoiding invasive species. You can find a full list of invasive species developed by the California Invasive Plant Council. Remember when buying plants to make sure to check the scientific name so that you are getting the species you want!

©Bryan Fernandez /Flickr; Invasive fountain grass (Pennisetum setaceum) in the Santa Monica Mountains.

We created below a list of the most common invasive species in southern California. This list is non-exhaustive and we encourage you to consult our Resources section for additional information.

Photos of the plants listed are courtesy of the California Native Plant Society and the Theodore Payne Foundation.

Invasive Trees of Southern California

| Edible Fig Ficus carica |

False Sandalwood Myoporum laetumn |

Pepper Trees Schinus spp |

||

|

|

|

||

| Can be a problem in the San Francisco Bay area, the Central Valley, and southern California. May be spread by birds and deer, as well as by vegetation fragments. Can dominate stream and riverside habitat. | Invades along the coast from Sonoma County to San Diego. Forms dense stands with no other vegetation. Can cover large areas. Spread by birds. Leaves and fruits are toxic to wildlife and livestock. Burns easily. Doesn’t typically spread in interior areas. | Pepper trees are native to South America (despite the fact that Peruvian peppertree is sometimes called California peppertree). Seeds are transported by birds and mammals into natural areas. The aggressive growth of peppers enables them to displace native trees and form dense thickets in natural areas. They produce undesirable suckering and sprout unwanted seedlings. A serious problem in southern California. Less of a problem in the San Francisco Bay Area and Central Valley, but care should be taken if planting near wildlands. |

Tree of Heaven Ailanthus altissima |

Eucalyptus Trees Eucalyptus globulus |

Russian Olive Elaeagnus angustifolia |

||

|

Eucalyptus globulus Eucalyptus globulus |

|

||

| Although not commonly sold in nurseries, this tree is sometimes “shared” among gardeners. Tree-of-heaven produces abundant root sprouts that create dense thickets and displace native vegetation. These root sprouts can be produced as far as 50 feet away from the parent tree. In California, it is most abundant along the coast and Sierra foothills, as well as along streams. A single tree can produce up to a million seeds per year. | Found along the coast from Humboldt to San Diego and in the Central Valley. Most invasive in coastal locations. Easily invades native plant communities, causing declines in native plant and animal populations. Fire departments throughout Southern California recommend against using eucalyptus trees for landscaping because they are extremely flammable. | Found throughout California. Able to spread long distances with the help of birds and mammals. Invades river and stream corridors, pushing out native willows and cottonwoods. Reduces water levels. Provides poor wildlife habitat. Serious invader in other western states. |

Tamarix /Saltcedar Tamarix aphylla, Tamarix parviflora, Tamarix ramosissima |

Hawthorn Crataegus monogyna |

|||

|

|

|||

| A serious invader throughout California and southwestern states. Uses excessive amounts of water, increases soil salinity, changes water courses. Diminishes wildlife habitat, and increases fire hazard. Not commonly sold but still occasionally available. | An established invader of the Pacific Northwest, now spreading through northern California. Capable of long-range dispersal by birds. Creates dense thickets, changing the structure of woodland understories. May hybridize with and threaten native hawthorn species. |

Invasive Palms of Southern California

| Canary Island and Mexican Fan Palms Phoenix canariensis, Washingtonia robusta |

||||

|

||||

| Most palms are good garden plants, but Mexican fan palm and Canary Island date palm are extremely invasive. In Southern California, they invade wetland areas, crowding out native vegetation. Canary Island date palm seeds are spread by birds. Dense groups of palms with untrimmed fronds harbor rats and snakes and can be a fire hazard. |

Invasive Shrubs of Southern California

| Acacias and wattles Acacia dealbata and Acacia melanoxylon |

Brooms Genista monospermabridal, Genista monspessulana, Cytisus striatus, Cytisus scoparius, Spartium junceum |

Scarlet wisteria / Red sesbania / Rattlebox / Chinese wisteria Sesbania punicea |

||

|

|

|

||

| Acacias grow along most of the coast and inland in the central portion of the state. They spread by seed, root, suckers, and stump sprouts, forming dense stands. In southern California, coastal wattle (Acacia cyclops) has invaded many natural areas incluing wetlands and dry hillsides. | Brooms have invaded over one million acres in California. The flowers produce thousands of seeds that build up in the soil over time, creating dense thickets that obliterate entire plant and animal communities. Grows quickly, creating a fire hazard in residential landscapes. “Sterile” varieties haven’t been independently verified or tested and are not recommended as substitutes. | New to California, spreading along the American River in central California. Also found in the Delta and in northern California. A serious problem in South Africa and Florida. Grows and spreads rapidly along river and stream corridors. Pushing out native vegetation and wildlife. Seeds are moved by washing downstream or are carried by birds. |

Black Mustard Brassica nigra |

||||

|

||||

| Is a winter annual herbacious shrub. It grows profusely and produces allelopathic chemicals that prevent germination of native plants. The spread of black mustard can increase the frequency of fires in chaparral and coastal sage scrub, changing these habitats to annual grassland. |

Invasive Ornamental Grasses of Southern California

| Giant Reed Arundo donax |

Pampasgrass / Jubatagrass Cortaderia sp. |

Fountain grass Pennisetum setaceum |

||

|

|

|

||

| This grass grows along streamsides, where it can reach over 20 feet tall. It grows in dense thickets that clog waterways and is a fire hazard. When clumps of arundo are washed downstream during storms, they become trapped against bridges and create a maintenance problem where they land. Arundo creates less shade than the native trees it replaces, increasing water temperatures to a level that is dangerous for native fish. | Wind can carry the tiny seeds of these plants up to 20 miles. The massive size of each pampas grass plant with its accumulated litter reduces wildlife habitat, limits recreational opportunities in conservation areas, and creates a fire hazard. | Spreads aggressively by seed into natural areas by wind, water, or vehicles. Fast grower; impedes the growth of locally native plant species and eventually takes over natural areas. Also raises fuel loads and fire frequency in natural areas. Is spreading rapidly in California. Existing research indicates that red varieties of fountain grass P. setaceum ‘Rubrum’ are not invasive. |

Invasive Ground Covers of Southern California

| English Ivy Hedera helix |

Highway Iceplant Carpobrotus edulis |

Periwinkle Vinca major |

||

|

|

|

||

| Some ivy species in the Hedera genus are a problem in California. They can smother understory vegetation, kill trees, and harbor non-native rats and snails. It’s difficult to distinguish problem species from less invasive ones. Do not plant ivy near natural areas, never dispose of ivy cuttings in natural areas, and maintain ivy so it never goes to fruit. Researchers hope to determine which ivies can be planted safely. | This vigorous groundcover forms impenetrable mats that compete directly with native vegetation, including several rare and threatened plants. Small mammals can carry seeds of iceplant from landscape settings to nearby natural areas. Pieces of the plant can be washed into storm drains and into natural areas where they become established. | This aggressive grower has trailing stems that root wherever they touch the soil. Their ability to resprout from stem fragments enables periwinkle to spread rapidly in shady creeks and drainages, smothering the native plant community. |

Check your local nursery, landscape contractor or county’s UC Cooperative Extension service for advice on fire-resistant plants that are suited for your area.

Sources:

BeWaterWise (2015) – Fire-resistant California Friendly Plants

CALFIRE (2019) – Fire-Smart Landscaping

California Native Plant Society – CALSCAPE

G3 Watershed Approach to Landscape Design – California Watershed Approach to Landscape Design

Las Virgenes Municipal Water District (2009) – A California-Friendly Guide to Native and Drought Tolerant Gardens

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – Pests in Gardens and Landscapes: Quick Tips – Less Toxic Insecticides

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – Natural Environmental Pests

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – What Is Integrated Pest Management (IPM)?

©Elisa Read; Caspers Wilderness Park, Orange County, CA.

Protected Plant Species of Southern California

Approximately one-fourth of our more than 2,000 Southern California plant species are rare, endangered, or highly restricted in distribution. There is both good news and bad news regarding biodiversity in Southern California as a relatively large portion of the land area in the State enjoys protected status. However, although more than 80 percent of the area of high mountain conifer forests and alpine habitats is protected, other ecosystems such as wetlands, riparian woodlands, and coastal ecosystems – that are under increasing pressure from development and urbanization – face a different reality. Rapid urban and suburban expansion along the Southern California coast and in the WUI have led to a loss of the vast majority of coastal sage scrub and the associated endangered plant species.

©Elisa Read

Preservation of Southern California biodiversity must rely not only on public agencies but also on residents and landowners of these sensitive areas. Federal and state regulations have been established to protect rare and endangered plants and animals that live in wildfire country. Whenever there is any doubt about clearing or thinning native brush, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and California Department of Fish and Wildlife should be consulted.

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife

California’s Threatened and Endangered Species

State and Federally Listed Endangered, Threatened, and Rare Plants of California

- Find Endangered Species

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Endangered Species portal

©bgwashburn / Flickr; Nuttall’s Woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii) in Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia).

Oak trees (Quercus spp.) are recognized as significant historical, aesthetic, and ecological resources in California. There are 40 species of native oaks found throughout California on approximately 20 million acres in widely different areas: the central valley, lower foothills, mixed coniferous zone and coastal mountains. Not only are oak woodlands beautiful, they are surprisingly productive communities. More than 330 species of animals (and thousands of insect species!) use oak habitats for some part of the year. As with almost all natural habitats in California, oak woodlands currently face a number of threats and uncertainties. These include concerns about poor regeneration, competition from invasive species, native and introduced pests, habitat loss, changes in land use, threats from fire, and climate changes.

| Coast Live Oak Quercus agrifolia |

Scrub Oak Quercus beberidifolia |

|

|

|

|

| This evergreen tree provides deep, wide shade with holly-like leathery dark green leaves, tooth edged, 1-3” long. Thick moist bark helps protect tree against fires. | A large shrub with dense growth, variable leaves, usually ¾ – 1½” long, medium green on top, grayish on bottom, and wavy edges. Good as clipped hedge or background. |

Valley Oak Quercus lobata |

Interior Live Oak Quercus wislizenii |

|

|

|

|

| This deciduous tree with crooked branches and checked gray bark is a trademark of valley grasslands. Leaves are deeply cut, round-lobed 3-4” long, 2-3”wide, dark green on top, paler on bottom. Tolerant of heat. | A tree with a dense, rounded crown, is often wider than high. Glossy, elliptical, green leaves are 1-4” long with smooth or spiny edges and abruptly pointed tip. Tolerant of shade. |

Oak Trees and Fire

Oaks are integral to California’s native ecosystems, making the health and survival of our native oak species particularly important. Fortunately, oaks have evolved mechanisms to survive periodic burning, since fire is a natural element of oak ecosystems. With low- and even moderate-intensity fires that scorch all the leaves on native oaks, little or no long-term damage typically occurs. Even fully burned oaks often will re-sprout and recover over time. When fires occur in the summer and fall, native oaks usually will not produce a set of new leaves until the following spring. Following such fires the trees may appear dead, since all the leaves are brown and brittle and the trunks may be blackened. Many of these trees will survive.

Oak woodlands are less prone to ignition than many common non-native trees including eucalyptus, pepper trees and some pines. The large full canopy of oak trees can catch and deflect embers. The RCDSMM is currently working with a partner organization to model typical wind scenarios in the Santa Monica Mountains to help us better understand the role native trees could provide in buffering and deflecting wildfires.

Re Oak California

California’s oaks are the powerhouses of our ecosystems, but disease and habitat destruction have put oak populations in serious decline. Now, Californians are coming together to restore this vital natural resource. With a few simple actions, you too can be part of the solution. Here’s how you can help:

Collect acorns: Since the devastating 2017 fires in wine country, thousands of Californians have gathered acorns for oak restoration efforts. It’s a simple, fun way you can make a difference when acorns drop in the fall. Get instructions by signing up at cnps.org/acorns.

Adopt an oak: Plant an oak (or a collection of oaks) on your property with locally appropriate oak species. For example, thanks to the many volunteers who’ve helped collect acorns, the RCD of the Santa Monica Mountains, TreePeople, Sky Valley Volunteers and other local groups have been planting oaks throughout the Santa Monica Mountains. To find out how to care for and grow an oak from an acorn into a self sustaining tree, go to How to Grow California Oaks (UC ANR).

If you want to adopt a baby oak tree, go to Caring for Your Native Trees.

Attend or host a planting event: Community partners, schools, and neighborhoods are signing up to host oak planting events. Organize your own or find out about events near you.

Make a donation to help plant and grow oaks! Go to Adopt an Oak (Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains)

©Calscape 2017 – Zoya Akulova; Coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia)

Oak Tree Ordinances

The state of California bans the removal of certain native trees, including oak trees. Multiple jurisdictions in California have adopted Oak Tree Ordinances to create favorable conditions for the preservation and propagation of this unique and threatened plant heritage. In Los Angeles County, the Los Angeles County Oak Tree Ordinance applies to all unincorporated areas of the County. Individual cities may have adopted the county ordinance or developed their own ordinance which may be more stringent. Please check existing ordinances and requirements with your local jurisdiction. Below are examples and links to LA County and Ventura County ordinances.

Los Angeles County Oak Tree Ordinance

Under the Los Angeles County Ordinance, a person shall not cut, destroy, remove, relocate, inflict damage, or encroach into the protected zone of any tree of the oak tree genus, which is 8″ or more in diameter four and one-half feet above mean natural grade or in the case of oaks with multiple trunks a combined diameter of twelve inches or more of the two largest trunks, or remove branches over 2″ in diameter, without first obtaining a permit.

More information

Los Angeles County – The Los Angeles County Oak Tree Ordinance

Los Angeles County Regional Planning – Oak Woodlands Conservation Management Plan

Ventura County Tree Protection Ordinance

The Ventura County Non-Coastal Zoning Ordinance regulates the removal, trimming of branches or roots, or grading or excavating within the root zone of a “protected tree.” Altering or removing a tree without the required permit is punishable as an infraction or a misdemeanor. Costs for replacing trees may also be charged to the landowner or responsible party. Any oak or sycamore tree with a single trunk measuring 9.5 inches or more in girth (circumference) is protected.

More information

Ventura County – Ventura County Tree Protection Ordinance

Additional Information

CALFIRE – Oak Woodlands

California Wildlife Foundation – Fire in the Oak Wild Lands

California Native Plant Society – Fire Recovery Guide

Los Angeles County Fire Department – Oak Trees: Care and Maintenance

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – Burned Oaks: Which Ones Will Survive?

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – Living Among the Oaks: A Management Guide for Woodland Owners and Managers

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – Oak Woodland Management Portal

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – Protecting Homes from Wildfire in Oak Woodlands

University of California, Agricultural and Natural Resources (ANR) – The Cultural Values of Oaks

©Elisa Read; Drought tolerant landscapes with sticky yellow monkey-flower (Diplacus longiflorus).

What is “Hydrozone” Planting?

Group Plants by Water Needs (Hydrozone) and Plan Ahead for Maturity.

Proper plant placement, taking into account mature plant size, should limit the need for future pruning and reduce the amount of maintenance required in the long run. Natural forms are encouraged for habitat value, but fire prevention does require pruning and removal of dead, diseased, damaged and decayed plant material.

- Plants with similar cultural and water requirements should be planted together.

- Consider the soil, water needs, sun/shade and temperature requirements for each hydrozone.

- Do not mix plants with different water requirements in the same hydrozone.

- The irrigation of each hydrozone should have matched precipitation (every nozzle needs to emit the same gallons per minute for spray or gallons per hour for drip).

To learn more about the irrigation water needs for over 3,500 taxa (taxonomic plant groups) used in California landscapes:

- University of California, Department of Agricultural and Natural Resources – Water Use Classification of Landscape Species (WUCOLS)

- It is based on the observations and extensive field experience of thirty-six landscape horticulturists and provides guidance in the selection and care of landscape plants relative to their water needs.

- The WUCOLS project was initiated and funded by the Water Use Efficiency Office of the California Department of Water Resources. Work was directed by the University of California Cooperative Extension, San Francisco and San Mateo County office.

Sustainable Irrigation

©Saxon Holt/PhotoBotanic

Grey water and recycled water for irrigation

As drought conditions become increasingly likely over time, it’s essential that we all learn to use water more efficiently. Using grey water or recycled water can help to conserve our finite water resources. Grey water can be safely used to water landscape plants and orchard trees.

In California, washing machine systems that do not alter the house plumbing can be built without a construction permit as long as certain guidelines are followed. In a typical laundry-to-landscape system, the water should enter the landscape at the drip line of plants with a good cover of mulch. The system’s discharge points themselves must be covered with a 2 inch layer of mulch, stones or a plastic shield. Grey water must not be used in a sprinkler system.

For more information:

- EcologyCenter.org – Greywater and Rainwater Harvesting Resources

- GreyWaterAction.org – Basic Greywater Guidelines

- HarvestingRainwater.com – Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands

- University of California, Department of Agricultural and Natural Resources (2020) – Use of Grey Water and Recycled Water for Irrigation

- University of California, Department of Agricultural and Natural Resources (2015) – Use of Graywater in Urban Landscapes in California

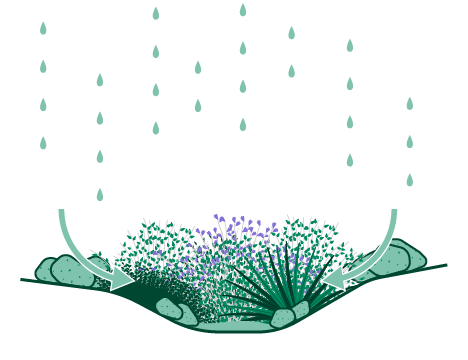

Rain gardens

As cities and suburbs grow and replace forests and agricultural land, increased stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces becomes a problem. Stormwater runoff from developed areas increases flooding, carries pollutants from streets, parking lots and even lawns into local streams and lakes, and leads to costly municipal improvements in stormwater treatment plants. By reducing stormwater runoff, rain gardens can play a valuable part in changing these trends. Compared to a conventional patch of lawn, a rain garden allows about 30% more water to soak into the ground.

Consult your local Planning Department as following these Best Management Practices (BMPs) including rain barrels / small cisterns, rain tanks, permeable or porous pavement systems, rain gardens and dry wells may require a permit.

For more information:

- BeWaterWise (2018) – How to Make a Rain Garden, California Friendly Landscapes

- EcoMalibu (2018) – How To Construct a Rain Garden

- University of California Cooperative Extension, Sonoma County Master Gardeners – How to Build a Rain Garden

- University of California, Department of Agricultural and Natural Resources (2015) – Coastal California Rain Gardens

Rain barrels and cisterns

Rain barrels and larger cisterns help residents to collect and reuse rainwater from roofs and gutters, retaining water on-site, and reduce the amount of pollutants that flow into storm drains and local waterways. Every gallon of rainwater that is collected in rain barrels saves one gallon of drinking water that would normally be used for irrigation. For every inch of rain that falls on Los Angeles, 3.8 billion gallons of runoff flows to the ocean. A roof is an ideal catchment area to divert the rain – using gutters, downspouts and rain chains into a tank or rain barrel, and serve as water source for your native and drought tolerant garden.

Consult your local Planning Department as following these Best Management Practices (BMPs) including rain barrels / small cisterns, rain tanks, permeable or porous pavement systems, rain gardens and dry wells may require a permit.

You can find more information about rain barrels following the links below:

- Las Virgenes Municipal Water District – Rain Barrel Installation Guidelines

- SoCal WaterSmart – Residential Rebates for Rain Barrels and Cisterns

- TreePeople – Capturing and Infiltrating Rainwater

- West Basin Municipal Water District – Capturing and Infiltrating Rainwater

Turf replacement programs

Turf grass is one of the most water-intensive plants in your landscape. By replacing your lawn for landscape, you could save on water bill, maintenance costs, and show that you care about conserving water.

You can find more information following the links below:

- BeWaterWise – Turf Replacement Program

- Los Angeles Department of Water and Power – Turf Replacement Program

Identifying & Removing Lawn Types:

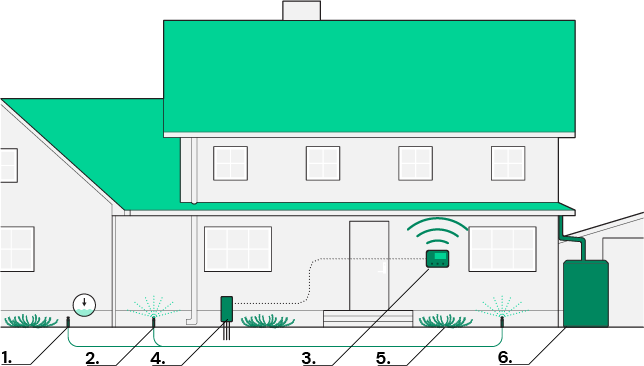

Smart Irrigation Systems

You don’t have to choose between maintaining a beautifully landscaped property and conserving water. There are solutions that will let you be a good neighbor, while saving water and money.

|

Low pressure / drip-irrigation system Designed to reduce inefficiencies and water loss, they deliver water directly to where the plants need it, with little or no evaporation, overspray and runoff. They include drip systems (micro-sprayer, bubblers, and emitters), inline emitter tubing, and soaker house. Since drip irrigation is covered with soil or mulch, water does not evaporate as quickly as it might if it were applied at the surface by spray. Installations of subsurface (or under at least 2 inches of mulch) systems may be the most efficient way to irrigate nearly every type of garden area. Since the tubing is flexible, it can be made to accommodate a wide variety of irregularly shaped areas or rectangular areas when laid in a grid pattern. |

|

Rotating sprinkler nozzles A high-pressure, multi-trajectory, rotating streams apply water more slowly and uniformly to your landscape, encouraging healthy plant growth. This can be an efficient way to irrigate large landscapes with groundcover or uniform plant material like lawns or meadows.When properly installed, low volume spray heads apply water at about 1/3 the rate of conventional spray heads. The newer spray irrigation heads are improved so that they spray heavier water droplets that are more resistant to wind. Landscapes with grade changes using spray heads should have check valves installed to prevent water from flowing out of the heads at the lowest point in your landscape. |

|

Weather-based irrigation controller Allows for accurate, customized irrigation by automatically adjusting the schedule and amount of water in response to changing weather conditions. |

| Soil moisture sensor system A soil moisture sensor measures soil moisture content in the active root zone on your property. |

©Antoine Kunsch; Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus).

What is Integrated Pest Management (IPM)?

Insects, diseases, and invasive weeds threaten California’s natural environments as well as homes, gardens, and agriculture. This page contains links to articles, fact sheets, and other information prepared by UC scientists on topics related to pests in natural environments.

An Integrated Pest Management -or IPM- is an ecosystem-based strategy that gardeners can use to solve pest problems while minimizing risks to people and the environment. A fundamental concept of IPM is that a limited amount of pest damage to plants can be tolerated. Home gardeners using IPM strategies are usually willing to accept minor insect damage to avoid pesticide application. IPM can be used to manage all kinds of pests anywhere, from urban or agricultural areas to wildlands.

The University of California defines IPM as:

“An ecosystem-based strategy that focuses on long-term prevention of pests or their damage through a combination of techniques such as biological control, habitat manipulation, modification of cultural practices, and use of resistant varieties. Pesticides are used only after monitoring indicates they are needed according to established guidelines, and treatments are made with the goal of removing only the target organism. Pest control materials are selected and applied in a manner that minimizes risks to human health, beneficial and nontarget organisms, and the environment.”

©Elisa Read; Acmon blue (Icaricia acmon) on California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum).

Integrated Pest Management Recommendations

Identify your pest

Pest identification is always the first step in IPM. The University of California has developed resources to help gardeners identify their pests and find the most effective and sustainable treatment methods. Consult the pages below if you need help with pest identification:

Nonchemical Control Options – Alternative to Pesticides

For home gardeners, especially for those living in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI), we encourage the use of nonchemical control methods such as cultural practices, mechanical barriers, and biological controls. These control methods are described in details in the UC Master Gardeners program.

- Biological control: Biological control is the use of natural enemies – predators, parasites, pathogens, and competitors- to control pests and their damage. Invertebrates, nematodes, and vertebrates have many natural enemies. Biological control is usually used to control insect pests as they are relatively few natural biological control agents for plant pathogens and weeds.

- Cultural controls: Cultural controls are practices that reduce pest establishment, reproduction, dispersal, and survival. They are modifications of normal plant care activities aimed at reducing or preventing pests. For example, changing irrigation practices can reduce pest problems, since too much water can increase root disease and weeds. Other techniques include digging, tilling and cultivating, crop rotation, and garden diversification. It is important to match the most effective cultural control with the pest you identified.

- Mechanical controls: Mechanical and physical controls kill a pest directly, block pests out, or make the environment unsuitable for it. Traps for rodents are examples of mechanical control. Physical controls – also called environmental controls – include mulches for weed management, steam sterilization of the soil for disease management, hot water dips, soil solarization, or barriers such as screens to keep birds or insects out.

©Elisa Read; Ladybugs (Coccinellidae sp.).

Chemical Control – Less Toxic Pesticides

In cases where nonchemical control methods are unsuccessful, pesticides are used in combination with other approaches for more effective, long-term control. Pesticides are selected and applied in a way that minimizes their possible harm to people, nontarget organisms, and the environment. With IPM you’ll use the most selective pesticide that will do the job and be the safest for other organisms and for air, soil, and water quality; use pesticides in bait stations rather than sprays; or spot-spray a few weeds instead of an entire area. The first choices for any home gardeners to control pests should include:

-

- soaps (potassium salts and fatty acid)

- insecticidal oils

- microbial insecticides

- botanical insecticides

Chemical Control – Pesticides to Avoid

The following pesticides are highly toxic to a wide range of organisms including beneficial insects and gardeners’ allies. They are also a safety concern for humans when used improperly.

-

- Pyrethroids such as permethrin, cyfluthrin, cypermethrin, and bifenthrin are synthetic versions of pyrethrins and can move into waterways and kill aquatic organisms.

- Organophosphates such as malathion, disulfoton, and acephate are highly toxic to natural enemies.

- Carbaryl, the active ingredient in older Sevin products, harms bees, natural enemies, and earthworms.

- Systemic neonicotinoids (such as imidacloprid and dinoteferan) can be very toxic to bees and parasitic wasps, especially when applied to plants that are flowering.

- Metaldehyde, a common snail bait, is toxic to dogs and wildlife. Use iron phosphate baits instead.